In a recent blog post I shared the exciting news that my short story, Shriek Song, has been published in the recent edition of New Writing Scotland.

Shriek Song follows the encounter between a girl and a banshee during a wild storm in the Irish countryside. In writing my short story collection about women and the female tongue, and with my interest in myths and landscapes, it didn’t take long for me to realise that I just had to write a story about a banshee.

In this blog post I’ll share some of my research to provide a brief history of the banshee, and explain why the mythical figure is so fascinating and ripe for re-interpretation in the modern day.

Bean sídhe: woman of the fairies

A distinctly Celtic myth, the banshee crops up in Irish (and in differing forms in Scottish and Welsh) folklore as a mysterious female creature whose scream is said to herald something terrible, or to mark something terrible having already happened – specifically that a member of your family is going to die. There are also tales of soldiers fleeing battlefields after the sound of her ghastly wail. Essentially, if you hear the cry of a banshee, it’s not good news.

It is said that the Irish word banshee comes from the Old Irish for ‘woman of the fairies’ or ‘woman of the fairy mound’: bean sídhe. The banshee, then, is undoubtedly connected to the fairy or spiritual world. Her cry heard in the human realm is a spooky reminder that there are things we cannot understand and – most spooky of all – things we can’t control.

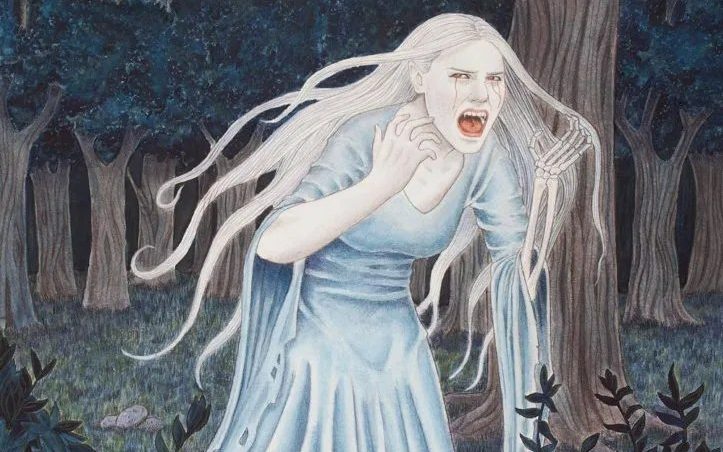

Something I found interesting when it comes to the banshee is that there are differing ideas of what she looks like. Some sources describe her glamorously: a beautiful young woman who tries to lure men with her good looks. Alternatively, she’s depicted as a dishevelled old crone with white hair, a fairy tale archetype of an evil spirit. Of course, a magical woman can only be stupendously beautiful or hideously evil; there is no room for in-betweens in myths. There are also reports of her wearing a cloak and having red eyes, although I’m not sure if that’s from being evil, or from all the crying.

While it seems like she’s described differently in various sources, I also read of her being able to transform between appearances by some accounts. In this way, her outward looks becomes something of an extra power for the banshee – a way to decide on her physicality and choose for herself what best fits the occasion.

Bean-nighe: the Scottish washerwoman

The Scottish version of a banshee is the bean-nighe, which means washerwoman. Distinctly less supernatural than her Irish cousin (although still just as frightening), the Scottish banshee is similarly an omen of death, but without all the screaming.

One of the most interesting differences between the bean sídhe and the bean-nighe is the domestic setting of the washerwoman. While the banshee seems free to roam the Irish lands at whim, dropping in to scream wherever she likes, the Scottish washerwoman is seen only around streams and pools where she is described as eerily washing the blood from the clothes of those who are about to die.

As we all know, sometimes it is the most familiar of things that can be most scary (see Freud’s The Uncanny for more – something I have referenced in just about every essay I’ve ever written). While the sheer unknown of the ghostly banshee is undoubtedly scary, there’s something intangible about her that makes her feel removed from everyday life. The washerwoman washing clothes by the stream, however, is an image familiar to all. The mundanity of her activity is known, the process understood. So I would argue that to encounter the Scottish banshee might be even more frightening than the Irish version.

The lament of a keening woman

One of the reasons I became so fascinated with the idea of a banshee is the sheer amount of words used to describe the noise she makes:

- wail

- shriek

- scream

- cry

- lament

- keen

- call

- screech

- roar…

…are just some of the verbs that crop up when it comes to talking about the banshee.

Fascinatingly, Shane Broderick categorises on their blog post the two different types of sounds the banshee is reported to make. While sorrow and mourning is imperative to the first group (wail, cry, lament, keen), the second group contains more wild, animalistic sounds: roar, shriek, screech. So what is the banshee then: an unhinged melancholy woman, or something more primitive?

Two particular terms spring to mind when discussing the banshee and those are lament and keening. Both of these are about mourning the passing of life, with a lament meaning an outpouring of grief, and keening being perhaps more specific to the crying out in grief, as opposed to lament‘s more general mourning.

Keening is a notably Irish tradition which used to be part of the Irish funeral ritual. While bards would traditionally perform the keen in a group setting, the term is now intrinsically tied up with the myth of the banshee who performs her keening alone, and to the terror of others. Human women who keen are “the (human) structural adjunct of the banshee” (Mary McLaughlin), and thus the idea of keening and lamenting becomes a particularly female phenomenon. Women are, of course, more prone to hysteria and outbursts of emotion as we all know. This is something I address in a separate short story in the same collection.

What’s interesting about the banshee is that, as a mythical creature, she is often reported to be seen and not heard. That idea of a distinctly female noise (a cry or scream) holding such fear and power over a group of people, especially when we consider the lack of power that real woman held in their voices throughout history, is intriguing to me. Does the banshee hold so much power because she’s female? Would her voice be as frightening if it were deeper and more man-like? And is it only because she’s magical that she’s listened to?

As you can see, there is so much to dissect and pick at when it comes to the banshee, or wailing woman. And although the myth is relatively well known, in the UK at least, it feels likes there aren’t many representations of the banshee in modern day writing (Harry Potter reference aside). While we’ve seen a recent uptake in novels and fiction about witches – witcherature, my new favourite word – I can’t help but wonder if the banshee deserves to hold the attention of the feminist gaze in 2022. And, of course, I hope that my story contributes something towards that.

Shriek Song: an ancient banshee in the modern world

In my story, Shriek Song, I wanted to explore the idea of a banshee through the narrative of a young woman who has recently experienced a sexual assault. In writing about the female tongue and focusing my stories on different noises (cry, howl, silence), the concept of a mythical creature who is known for her harrowing shriek was one that I couldn’t not address. And yes, I also did think about reinventing the song of the siren – but that story’s for another day (or collection).

As discussed, banshees are fearsome creatures whose voice is known to bring death, or represent something bad happening. To quote my own short story:

“The banshee is a warning and a premonition. Her cry is to let the world know that somebody is about to die. It’s the tolling of a bell. It’s a lamentation, a keening for the loss of life. It’s the sound that has haunted these shores since the beginning of time. It’s the sound you hope you never hear.”

In Shriek Song, the rural Irish community of my young protagonist is well aware of the banshee and what she means. There is an oral tradition that has passed down tales of the wailing woman: “The girl’s mother told her all the stories about the times the banshee has been heard shrieking. She can list them like a prayer.” Later, when the banshee is heard by the men in the pub, “they all pause, drinks on the way to their mouths, a shiver of fear running up the spines of those old enough to remember the last time.”

But what if the bad thing has already happened? What if my protagonist has been holding in her own scream for too long? What if – if you were the right person and you really listened to it – the scream didn’t sound like a scream, but a song?

Spoilers aside, I will always love writing about women’s voices and the way they sound and come out. Shriek Song is about repression and exaltation, and all the things in between. It’s about power and who gets to reclaim their own story, and voice. You can read the full story in New Writing Scotland by ordering a copy of the anthology here (perks of having a surname starting with W means I’m the grand finale!).

The joy of reinventing myths and fairy tales

When reinterpreting myths and fairy tales, I think always of Angela Carter and Marina Warner. In her famed short story collection, The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter breathed new life into dusty fairy tales, from Bluebeard to the Erlking, from Beauty and the Beast to Red Riding Hood.

The fairy tale genre has long been a safe space for contemporary writers to explore ideas at the core of human culture within a framework that is both recognisable and unreal, and the written form of fairy tales encompasses and blurs the boundaries between myth, folklore and oral traditions. While Angela Carter was the best of the best at examining things like sexuality and gender through her gothic fairy tale revisions, most often with a deliciously shocking twist, I see modern day writers such as Daisy Johnson, Julia Armfield and Lucie McKnight Hardy (to name a few) echoing this in their own work.

One of my favourite quotes from writer and self-proclaimed ‘mythographer’ Marina Warner is that “myth has both the power to entrench social prejudice and injustice, and the power to emancipate”. There is so much to look at when it comes to reinventing and reimagining the myths and fairy tales embedded within our culture, it really is a bubbling cauldron of opportunity. I very much hope that in speaking and writing about figures such as the banshee in the modern world, we are continuing along the journey of challenging what we know, and setting women free.

SOURCES USED

https://www.irishpost.com/life-style/exploring-irish-mythology-banshee-170287

https://www.scotclans.com/pages/the-bean-nighe

https://irishfolklore.wordpress.com/2017/10/22/the-banshee/

The Lore of Scotland: A Guide to Scottish Legends by Jennifer Westwood and Sophia Kingshill

Keening the Dead: Ancient History or a Ritual for Today? by Mary McLaughlin